Frederick Douglass

c. February 1818 – February 20, 1895

American orator, writer, abolitionist, and statesman

Major works: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881)

Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895) was born into slavery around February 1818 in Maryland. At a young age, he was taken from his home to live and work on a plantation, and subsequently rented by his master to a family in Baltimore where he was taught the alphabet and learned to read. During his later teen years, he was sent to work for a notorious “slave breaker” as a punishment for teaching other enslaved people to read.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped from slavery, traveling north through Newport, RI on the Underground Railroad. Once safely settled in Lynn, MA, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Douglass became an acclaimed orator and national leader in the abolitionist movement, publishing newspapers and traveling throughout the country and abroad giving lectures on the topic.

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.” – “West Indian Emancipation Speech,” 1857

Frederick Douglass was a leading intellectual force behind the American abolitionist movement and one of the most influential civil rights leaders of all time. His best-selling autobiographies laid bare the evils of American slavery and shaped the nation’s conscience.

In November 1841, less than three years after the Athenæum opened its doors, Frederick Douglass traveled to Providence to advocate for voting rights for Black men with abolitionists Parker Pillsbury, S.S. Foster, and Nathaniel P. Rogers. Although there is no record of Douglass himself visiting the Athenæum, member and abolitionist Thomas Davis introduced Pillsbury, Foster, and Rogers to the library during that trip. Davis is also notable for allowing Edgar Allan Poe to use his library membership to check out books in 1848.

On subsequent trips to Providence, Douglass visited library member Elisha Aldrich and his family. Aldrich’s daughter Amey, an avid lifelong Athenæum member herself, fondly remembered meeting the great orator: “Our house had a steady stream of visitors interested in the anti-slavery movement, the suffrage movement, and other then-unpopular great causes. We were waked up one night and taken downstairs in our flannel night gowns to sit in the lap of the distinguished negro, Frederic[k] Douglas[s], so we should always remember him.”

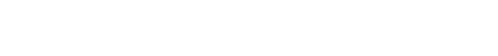

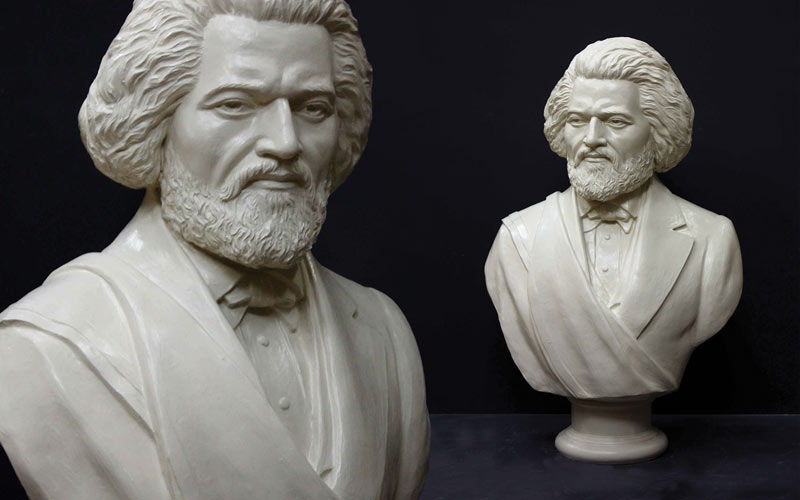

In 2019, the Athenæum commissioned a plaster copy of Johnson Mundy’s original marble bust of Frederick Douglass from artist Robert Shure of Skylight Studios in Woburn, MA. Mundy’s bust, commissioned by members of the Rochester community, was modeled from life and presented to the University of Rochester at a public ceremony on June 17, 1879. Douglass wrote to Mundy, “The more I look at the bust, the better I like it. There is a fullness and a completeness about it which I have not often found in that class of work… I am content to be made known through this specimen of your art to all who may come after me, and who may wish to know how I looked in the world.” While many photographs and representations of Douglass exist (he was the most photographed American in the 19th century), the Mundy bust was chosen as the Athenæum’s model both because of Douglass’ approval of the sculpture and because it captures him in 1879, at the height of his fame, influence, and abilities.

The process to reproduce the marble sculpture in plaster included a combination of artistic craftsmanship, 19th-century casting techniques, and 21st-century technology. The original bust is part of the collection at the University of Rochester, and in 2018 students created a 3D scan of the sculpture to celebrate the bicentennial of Douglass’s birth. Skylight Studios printed a rough model of Mundy’s bust in foam from a 3D printer, and then built up the portrait in clay before making a rubber mold and casting the final sculpture in plaster. The recreated bust is as faithful to the original marble as possible.